Reading time: 4 min.

Dr. Busch, you once said the following about the brain and movement: "The development of cognitive abilities begins with movement." What does that mean?

Yes, that's true. Because exercise brings about many factors that can significantly improve our cognition. These include improving blood circulation, oxygen supply and nutrition to nerve cells, and also the removal of metabolic waste products. And for several years now we have also known that physical exercise also triggers a series of growth processes in the brain, i.e. the formation of new nerve cells (neurogenesis) and the integration of them into a stable synaptic network.

This in turn can improve our mental performance. And several prospective studies that compared older, athletic people with their passive peers over a period of years have concluded that regular exercise can even increase our so-called cognitive reserve. Our mental decline is therefore delayed if we keep moving. External exercise promotes our internal exercise.

What does lack of exercise do to our brain?

Over 60% of the brain mass is associated with motor control. Intuitively, one might think that the human brain is primarily there for thinking. Strictly speaking, however, this is more of a secondary issue. Motor control requires much more neuronal activity and energy than thinking. Therefore, these areas still take up the most space today. However, if we hardly move in everyday life, these areas are no longer stimulated and some of them degenerate. There is a saving principle behind this: what is not functionally needed does not need to be fed with oxygen and glucose. In technical terms, this economic rule is: "Use it or lose it".

"Neuroathletic training could mean immense benefits for our patients, including those with a wide range of complaints and illnesses. Pain is just one example."

In your opinion, what should a movement that promotes neuroplasticity look like?

From everything we know so far, complex movements and motor processes are particularly stimulating for the brain and therefore also for neuroplastic growth. The strongest stimulation of nerve cells is surprise. This also applies to movements: this complexity is absent when walking. When climbing, dancing or doing athletics that require coordination, however, it is a central component of motor skills and means a constant influx of new signals that the brain has to process and respond to. This keeps nerve activity on its toes and increases the likelihood that newly formed nerve cells will survive longer.

What influence do perception and environment have on our brain

In digital worlds, we have to be careful that perception and learning do not remain too theoretical or limited to the two-dimensional screen. Here, too, movement helps us to better understand our environment: human cognition is "embodied"; this is known as embodied cognition . This means that our brain does not store objects, facts or complex situations in an abstract way, but almost always in connection with motor sequences and processes.

If you ask subjects to think of a hammer, the areas that are activated are less those in which the lexical meaning of the word is stored, and more those areas that have to do with the execution of the hammer movement.

Our brain stores and remembers things in the form of embodied memories. Of course, this only works if we have previously observed how to use a hammer or have done it ourselves. For this reason, sustainable learning is always linked to experience. Every theory requires the practice of implementation. This creates the embodiment of memories - and thus their long-term storage.

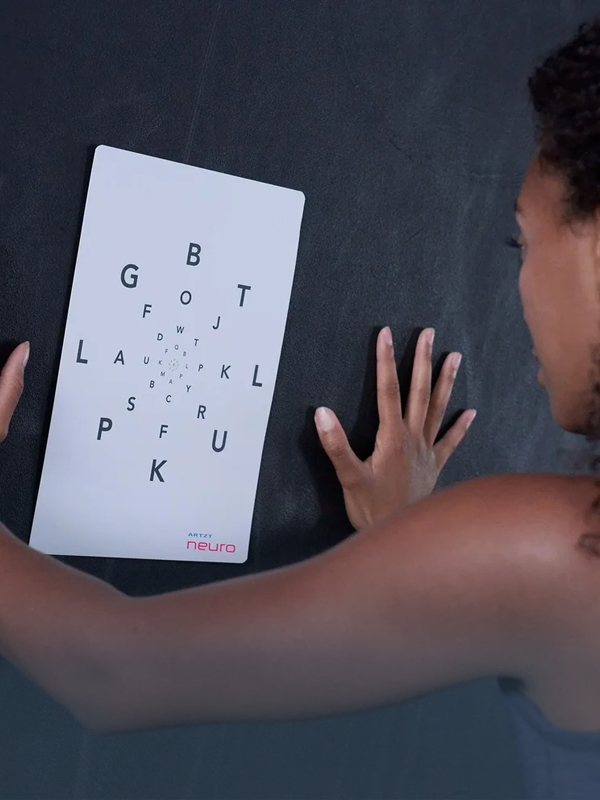

Neuroathletic training is currently in vogue. The focus here is primarily on perception and information processing as the basis for good and pain-free movement. Does this make sense to you from a neuroscientific perspective?

Neuroathletics and neurocentric training methods are the logical further development of the findings from laboratory studies on the influence of exercise on the nervous system. Their scientific effectiveness is still pending in many cases; we are still in the early stages here. Nevertheless, I think it is extremely important to deal with the topic in the form of application observations and, ideally, through controlled studies.

Neurocentric training could mean immense benefits for our patients, incidentally for a wide range of complaints and illnesses. Pain is just one example. In fact, this indication is particularly exciting. It is conceivable, for example, that the afferent inflow of highly complex proprioceptive and coordinative information during such training could support a neuronal reorganization of pain-processing areas in the brain.

This would then contribute to a restoration of the original structural conditions and consequently reduce pain, similar to what we already know from certain stimulus-physiological treatments for phantom pain and have even been able to prove neuronally.

About Prof. Dr. Volker Busch

Prof. Dr. Volker Busch is Speaker of the Year 2021, podcaster, bestselling author and specialist in neurology, psychiatry and psychotherapy and loves to focus on his passion: the world of mind and brain.

As head of a neuroscientific working group at the University of Regensburg, he and his team research the psychophysiological relationships between stress, pain and emotions and work therapeutically with people who suffer from various types of stress and accompany them on their path to mental health and satisfaction.

In addition, he has been passing on his knowledge and experience for many years in the form of keynotes/lectures, seminars and publications, helping managers, employees and his fellow human beings to achieve better brain health, motivation and inspiration.

In this way he creates a beautiful connection between literature, laboratory and people’s lives.

You can find out more about how the brain and movement are connected in the podcast episode The Moving Brain from Dr. Busch's podcast Brain Heard .